A significant, but not often discussed, loss of post-secular societies is the mysticism of the everyday. With millennia and the rise and fall of multiple civilisations, the gap between the divine and the mundane has grown wider and wider. Religion, as we know it today, is far more preoccupied with morality and the supernatural rather than the mythology that is behind the commonplace things that feature in our lives. It seems we have grown less interested in projecting divine meaning.

This was not always the case, and no other mythology or religion perhaps better exemplifies this projection than the Greek pantheon, which excelled in not only telling of how life was created but in why a spider spins a web as it does, why the seasons change or why the olive tree is among the most divine things on this planet. To remedy this separation, this article aims to bring you closer to the spiritual meaning of the items you use to garnish dishes, flavour your tea, or cook your food.

Honey, Ambrosia

Honey is not only the delicious byproduct of bees or the syrup drizzled on dessert, it's a favoured pet name we give to our partners and children. Our vernacular reflects our reverence, and fewer cultures have as much respect for honey as the Greeks.

Olympus’ gastronomy mainly consisted of two things: Ambrosia and Nectar, which translates as Immortality and Victory over Death, respectively. These two items were used for wine and honey and were coveted by every divine creature and mortal on Olympus and the surrounding lands. These commodities were associated with immortality and a long and prosperous life. Even bees were considered holy, supposedly acting as messengers for gods. Ambrosia is a pivotal resource in many tales throughout Greek mythology, spurring the victories of mortals and the ire of Gods in the likes of The Iliad and The Odyssey.

Regarding mortal doings, the understood divinity of the bees and their honey then translated into the sciences, with Greece being the first place to study Apiculture - beekeeping and honey production. Honey was also prescribed for wounds, fevers and diseases, as well as taken for enhancing physical performance by athletes. Greeks also, following the tales of Aphrodite – the goddess of love and beauty – and her self-care beauty routines, would use honey and beeswax as masks and balms for skin care.

Oregano, in honour of the Mountain

Another thing Aphrodite was famous for was her creation and cultivation of Oregano. High up in her Olympus garden she grew the soft-edged green herb and proclaimed it as a symbol of joy; its etymology in fact can be broken down to Oros and Ganos - Mountain Joy. From the etymology, we can infer that Aphrodite intended to have the herb act as a celebration for Mount Olympus, home of the gods and the de facto heaven of the Greek pantheon. Mirroring Aphrodite’s intent, couples getting married would wear crowns of Oregano, and the honoured herb was and is still used in medicinal practices and superstitious customs.

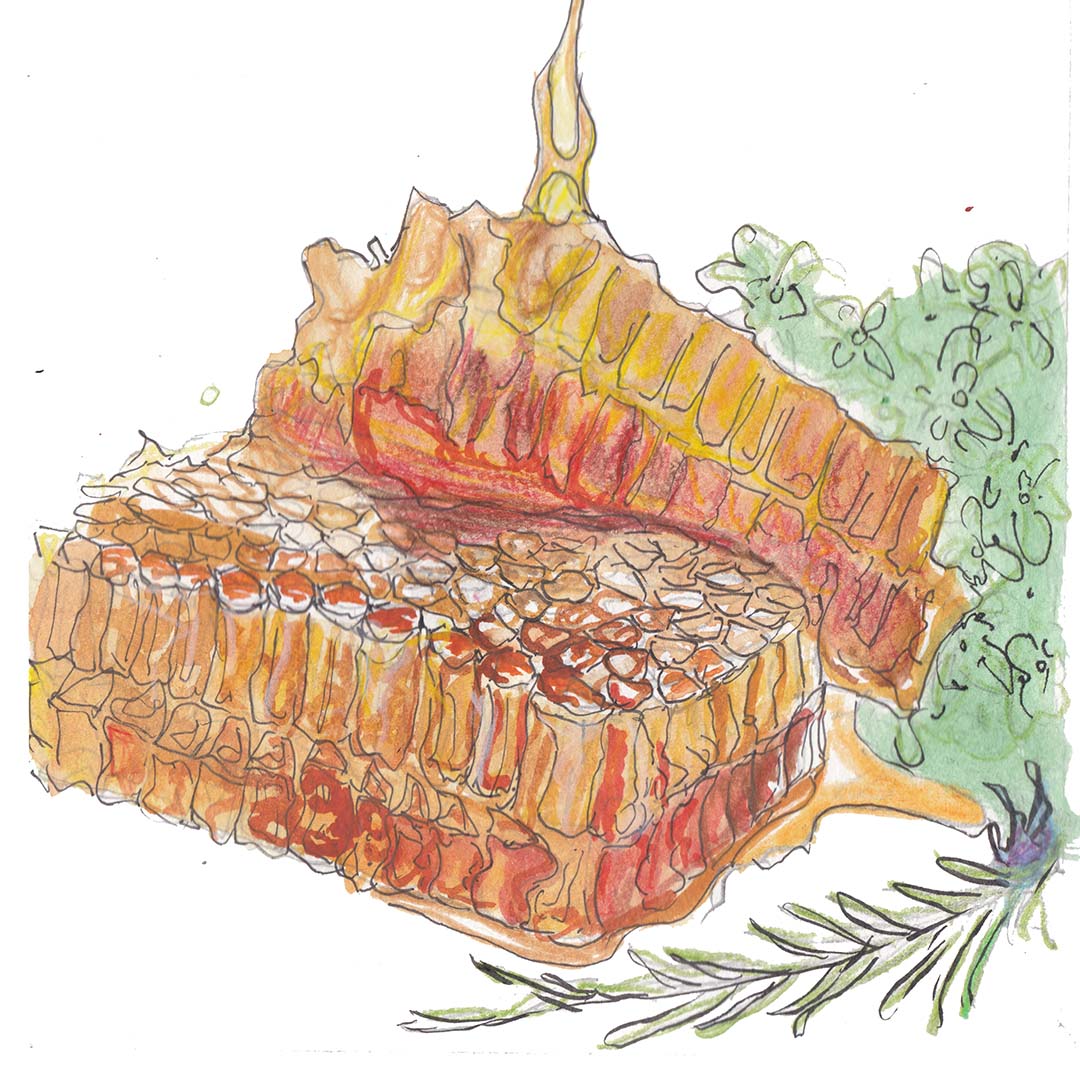

Rosemary & Thyme, Remembrance and Purification in Death

Both born from the mint family, Rosemary and Thyme are indigenous to the Mediterranean coast. Rosemary was supposedly brought there when Aphrodite, born of the severed genitals of Uranus cast into the sea, walked out of the water draped in garments made of the herb. While rosemary has been associated with more joyful practices such as foretelling the suitability of a romantic partner, it is also usually associated with remembrance, both joyous and melancholy. It was an aesthetic practice for Greeks who wove it in their hair, believing it would bring them better memory, but it is also used in burial and funeral traditions. This dour connotation was adopted by English culture, as well as perpetuated as a herb of grief by Shakespeare in the likes of Hamlet’s Ophelia and Romeo & Juliet’s Friar Lawrence, referring to suicide in Ophelia’s case and the death of Juliet in Lawrence’s.

It is not known why the Dew of the Sea – Rosemary’s Latin translation - has deathly connotations for the Greeks but it was shared by the Egyptians who sometimes scattered it in the tombs of the dead.

Rosemary isn’t alone in these deathly connotations, Thyme might be even more closely linked to the macabre. The herb was burned in rituals to purify religious sacrifices, burned at funerals and/or scattered in the coffins of the dead, as it was believed that the thyme would catch the soul and allow it to reside at peace within the herb as it passed from the mortal plane. It was also linked with rituals of courage, burning at an altar or hiding a sprig of thyme in one’s armour before a battle. One could infer that the courage lay in the belief that if one fell in combat, their soul was already purified enough to allow passage into the afterlife.

Olives and Olive Oil, Athens Child

A scene as divine as any other in Greek mythology graced the hill of Acropolis. Ten Gods sat it in council with the mortal King Kekropas at the centre, who wanted to find a suitable name for his kingdom’s great city. They chattered to one another as they awaited the two divine champions, whose gifts would compete against one another for the honour of naming the capital.

The first champion approached the circle, his muscles taut and dark under the Greek sun, and in his knotted hand he carried a regal and ornate Trident. His gait was confident and he smirked at each God before his gaze landed on the king. Poseidon, master of the sea, raised his trident and in a mighty roar, he struck its prongs into the earth, burying the steel into the crumbling rock beneath him. From the earth’s wound shot a geyser of seawater into the air, raining a mist onto Acropolis hill, and from the shadows of the waterfall a pearl-white mane sprung from the water and trotted around the King’s Counsel of Gods. They all applauded Posiedon’s display of might.

The geyser stopped spitting water and when the mist cleared the second champion approached the council. She moved with patience and composure, her tunic slacking on her body but never touching the ground. She stood beside the crack where Posiedon plunged his trident and smiled at each of her fellow Gods and King Kekropas. She kneeled on the ground and placed her hand on the wounded earth and closed her eyes. After a quiet moment, she moved her hand away, and a tree slowly sprouted and began to grow and branch and flower. And so the first Olive tree was born. Stunned by the display of modesty and grace, the Gods and the King declared Athena the winner, gifting the Goddess of wisdom the right to name the city. Athens was born. The olive tree prospered and spread and it is said every olive tree in the Attica area is a descendent of Athena’s gift.